That June 12, 1993 marked a watershed in the socio-political history of Nigeria is a given. The success and beauty of the presidential election which held that day remains a mystery of sorts, pleasant as it was.

I clearly remember the day as if it was yesterday, with nostalgic feelings. At that time, I was but a mere curb reporter, still cutting my teeth in journalism. Notwithstanding, the day was for me an unforgettable moment. I saw it all, from the benefit of participant observation and secondary information via media; information which I ravished with utmost pleasure.

The day was indeed a stanza in Nigeria’s efforts at instituting democracy that showcased the beauty the country could have become. Till today, I have not ceased to wonder over the miracle that day embodied. I also wonder whether it was an accident not meant to have happened.

June 12 was the culmination of a lengthy transition programme prosecuted by the Babangida Military Government to usher in democratic rule. As part of this process which started from 1986, governorship election was held in 1992, shortly after state assembly and local government elections in 1991.

After the military high command cancelled two presidential primaries over alleged electoral anomalies, it decreed two political parties, the Social Democratic Party, SDP, and the National Republic Convention, NRC. Two businessmen emerged candidates. While Bashorun MKO Abiola clinched the SDP ticket, Alhaji Bashir Tofa became the NRC flag bearer. Tofa picked a banker, Sylvester Ugoh as his running mate, while Abiola went for a diplomat, Babagana Kingibe.

The candidates, put forth interesting campaign messages that resonated with the people. At this time, Nigerians were being crushed by the Structural Adjustment Programme, SAP, of the Military Government, which was indeed sapping them. People were looking for a miracle that could pull them out of their miseries. They found hope in the presidential campaigns, particularly, Abiola’s Hope ’93 which promised to take the country out of poverty and want.

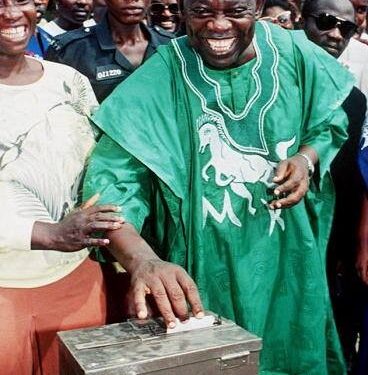

On Election Day, voters trooped out in large numbers. The voting method adopted was Option A4, a variant of the Open Ballot system. Introduced by Prof. Humphrey Nwosu, Chairman of the then National Electoral Commission, NEC, Option A4 required that voters queued behind the picture of their candidate. After the voting, the ballot papers were sorted out, counted and announced in the full glare of everyone.

My office had assigned me to cover the election in Ogbadibo Local Government Area. I left Makurdi on the eve of the election, arriving Otukpa, the headquarters of the local government at about 5 p.m. The excitement in the air could slap awake the dead. I saw people moving about, holding, swinging hands happily. Others sat in groups, discussing the election loudly, while sipping ‘palmy’. They all professed their readiness to participate in the voting.

When I eventually got to Orokam where I was billed to pass the night, the atmosphere was the same, electrifying! Though darkness had already crept in on the sleepy village, the people refused to notice. It was as if they were keeping vigil for the birth their saviour!

What elated me most about the interactions between the people was the frankness. No inhibitions. No quarrels. Nobody lost their cool enough to instigate anger. The only time I could link individuals to either of the parties was when they threw up clenched fists to shout Tofa! or MKO! Such shouts were devoid of bile or acrimony.

Read also: THE NATIONAL ANTHEM “AJUWAYA” – A COMIC EPIPHANY

On D Day, I woke early. Though there was restriction of movement, one of the privileges I enjoyed as a reporter was my classification as being on “essential duty” exempted from the ban. I contracted a motorcyclist in the village to take me round. We started with Owukpa District. People started moving to the polling centres early. Before June 12, it would be unthinkable for the people to abandon their farm work for anything. That day was different. Polling agents and clerks kept to the schedule. Satisfied with what I had seen at the polling units I visited at Ukwo, Itabono, Ugbugbu and Ede, I headed back to Orokam.

At Ipole-Oko, Ejema, Uture, Ako, Ukporo, Adupi and Adum in Orokam, the polling centres were filled to capacity, with people falling over themselves to be on queue. The sun was up but nobody cared. They patiently waited for their turn and performed their civic duty.

By the time I got to Otukpa, the counting of ballot papers had commenced. At Ijadoga, Epeilo, Court, Branch, Ogenago, and Orido, the jubilation bug in the air caught everyone. Only very few were seen with heads bowed, a slight sign of disappointment.

The news filtering in from other parts of the state and country conveyed the same atmosphere of free and fair conduct of the election. It was majorly violence-free. The few pockets of near-violent situations were easily nipped in the bud.

At the end of the day, the candidate of the SDP, MKO, was adjudged to have won the election, although there was no official declaration to that effect by NEC before it was annulled. That was how an election considered the freest, fairest, most people-driven, was deleted out of existence by what some attribute to hire wire political intrigue by the then military top brass and their collaborators within the political and business elite. The struggle to validate the election was a long drawn battle which consumed the lives of many, including the presumed winner. The only good thing that may have sprouted from that struggle is perhaps the declaration of the day as Democracy Day, now celebrated annually.

On June 12, 1993, violence during elections died. Voter apathy vanished. Tribal and religious bigotry went into hiding. More than anything, the spirit of one Nigeria came alive.

But, what is the secret behind the mystery of June 12? How did the nation achieve what happened that day? Why has that feat remained elusive ever since? Or could it be the spirit of MKO is still hovering around in anger, with a vow that the nation can never enjoy what it denied him?

Or, could it simply be that by 1993, the avaricious nature of the appetite of Nigerians, especially the elite and those in leadership positions, had not gained the despicably reprehensible status it has acquired over time? And if we cannot replicate June 12, what is the essence of celebrating it? Is it merely to remind ourselves of what could have been?